1. Humble beginnings

New York City already had its own marathon since 1970, an intimate affair looping around Central Park. It was normally attended by several hundred runners who would take four loops to complete the marathon distance. There was some hope of its profile expanding when none other than Kathrine Switzer brokered sponsorship with Olympic Airways.

The prize was tickets for the overall winner to fly to Greece and compete in the Marathon to Athens, held on the same course where the marathon legend was born.Unfortunately this deal only continued for one more year before succumbing to the chaos that ensued following the death of company owner Aristotle Onassis. Switzer and Fred Lebow, president of the New York Road Runners and the organiser of the 1970 event, had ideas of expanding the marathon beyond Central Park as early as 1974, but saw it as too difficult.

Then George Spitz entered the picture with far grander ideas. Spitz had tried repeatedly over the years to get into public office without success. Between elections, he made the fateful decision to train for and run the 1975 Boston Marathon. It was an event made famous that year for launching the career of winner Bill Rodgers, who unbelievably stopped several times to tie his laces on his way to victory. The question for Spitz was why New York City couldn’t have something of the same size and spectacle as what Boston enjoyed.

He began applying all the skills he’d acquired in his frustrated attempts to get elected to expanding the New York City Marathon to spread across the metropolis. Initially he was met with similar levels of success. One initial rejection came from Lebow himself. Spitz persisted, and the turning point was when he secured the support of the Manhattan borough president Percy Sutton. Sutton then secured financial backing through developers Jack and Lewis Rudin, who saw potential from the event expanding.

While things were looking positive, there was still quite the distance to go both literally and figuratively. New York City at the time was suffering through a major financial crisis and was risking going bankrupt. It was only through federal loans that the situation was turned around. Amidst this chaos, the mayor was convinced by the group that the reinvigorated marathon would help the city celebrate the bicentennial of the United States of America.

2. Everything comes together

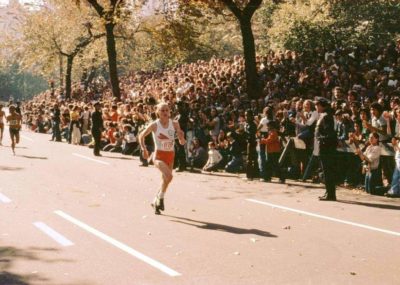

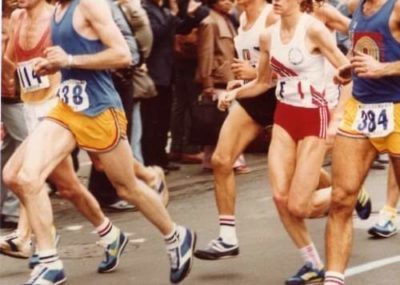

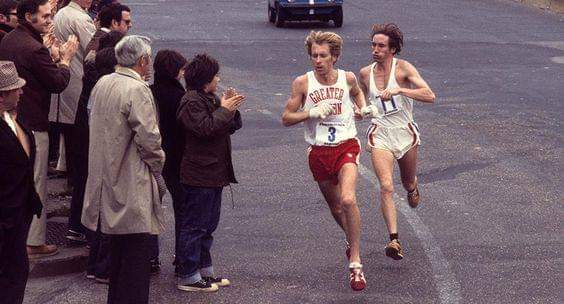

This was where Lebow took over, quickly securing the attendance of rising star Rodgers, and 1972 Olympic gold and 1976 silver medallist Frank Shorter. Shorter was significant in his own right, his victory at the Olympics having helped accelerate the boom in running through America. Momentum rapidly built, and by race day 2,090 men and women took the start, compared to just 339 the year before. Competitors were met with ideal conditions, overcast and cool. Joining Rodgers and Shorter was former world record holder and Commonwealth gold medallist Ron Hill.

Rodgers would take the lead around the 18 mile mark and would not let go, winning in 2:10:09, with Shorter more than three minutes behind. Wearing what were very likely Onitsuka Tiger Ohbori racing flats, he had also set the new American record in the process. It was redemption for Rodgers, who had failed to make the podium at the 1976 Olympics. There was one hairpin on the course that had Shorter symbolically passing the other way to Rodgers, the new star of American distance running being handed the torch by the former. Fellow running pioneer and Boston Marathon winner Miki Gorman would be the first woman past the finish in 2:39:11, good enough for 70th place overall.

Suffice to say, the event was an enormous success. Not only did athletes enjoy the challenge of running across the five boroughs of New York City, New Yorkers themselves embraced the event and the spectacle that it brought. Their enthusiasm added an additional challenge for runners, with crowds regularly spilling onto the course. The event would continue to grow, and bear witness to the debut of Grete Waitz in 1978. She came from nowhere to blitz the competition and set the new women’s marathon world record.

She continued finding more speed, and would be the first woman below 2:30 with her run in the 1979 event, going even faster again in 1980. It was great news for Adidas, with the blue and yellow Marathon 80 runners clearly visible to the throngs of cameras. Her performances attracted enormous attention, bringing women’s distance running even further into the spotlight. That year also saw the debut of Alberto Salazar, who had sensationally predicted that he would win and do so in under 2:10. Not only did Salazar beat a field including Rodgers and Gerard Nijboer, 1980 Olympic silver medallist and then world record holder, he finished in 2:09:41.

3. Plotting a different course

In 1981, the New York City Marathon became the event where both the men’s and women’s marathon world records were set. Salazar had promised that he would win and do so in record time. When he had crossed the line in first place, it was faster than the seemingly unbreakable pace that Derek Clayton had set in 1969. Allison Roe of New Zealand took yet more time of the women’s marathon world record, winning the event in a rare upset for Grete Waitz. It was an even greater achievement given she had undergone treatment on her right ankle for tendinitis only two days before the race.

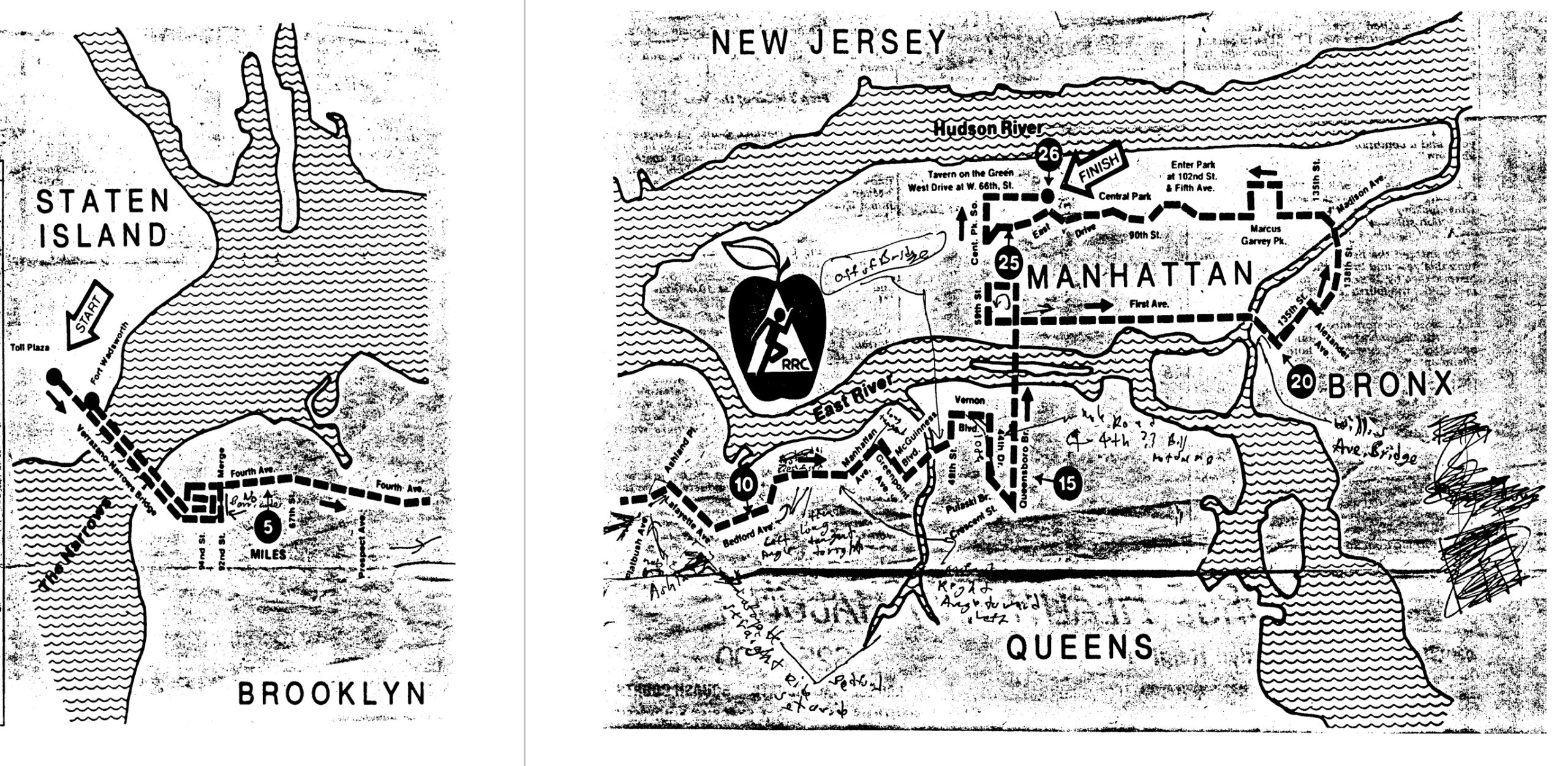

Although strictly speaking there was no official marathon world record like today, it was still significant for the event and its supporters. Not all was right however with the course the marathon plotted through the five boroughs of New York and eventually the organisers had to respond. It came down to the section through Central Park and how runners made their way through it.

Originally, local authorities had restricted competitors to the recreation lanes that were used for running during regular days, however in practice these limits were rarely followed. Lebow admitted that runners would get an advantage of around 50 metres by taking the shortest route. As it was, the new course for 1982 was 108 yards, or 99 metres, longer. This was not the first change the course witnessed, as organisers had made minor adjustments for the 1978 event.

Local construction work had required the course to take a different path as it entered Manhattan via 59th Street. In 1978 the path was cleared figuratively and literally, the course taking runners up First Avenue before turning back towards Central Park and the finish line. There was no suggestion then or later that the changes made any material difference to the length of the course.

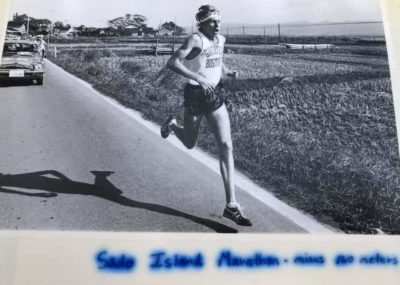

It was not the first marathon to fall afoul of road curvature. Multiple world records set at the Boston Marathon between 1951 and 1956 had to be invalidated for this reason. Due to improvements to the roads that straightened key parts of the course, the overall distance was found to be 1082 metres or 1183 yards, short. There was also the little-known demonstration race on Sado Island in Japan that Rodgers ran in the months following his victory in New York. He was invited by the leader of the drummer troupe Ondekoza, who trained by running and considered it as equally important to their music.

Founded in 1969, they introduced themselves to the world when they competed in the 1975 Boston Marathon, incredibly jumping on stage to perform once they passed the finish line. This was the same event Rodgers famously won, but in email correspondence he told me that he was likely invited by their leader, Tagaysu Den, either when he competed at the 1975 Fukuoka Marathon in December or at the 1976 Ohme-Hochi 30 kilometre road race in February 1976. At Sado Island, they would host a five leg relay race over the marathon distance against Rodgers running solo. We have one photo that shoes him wearing the red headband given to him by the troupe, marking him out as an honorary member.

In further email correspondence with Rodgers, he told me the course was flat and pleasant, easier than the New York City Marathon course he had just endured, and in perfect running conditions. The event was about fun, the distraction welcome after the stress of New York. Ahead of Rodgers was a truck with Ondekoza drummers playing their taiko drums. Rodgers would soon leave the relay runners behind, taking the lead by the second leg of the relay. Even though he was the only Westerner, cheering spectators waved both American and Japanese flags as he ran through the small villages along the route. When he crossed the line the time was initially 2:08:23. This would have been the world record, but Rodgers was informed soon afterwards that the course was around 130 to 200 metres short.

Even had the course been properly measured, it would not have been an official race. Nonetheless, had the course been the full marathon distance and Rodgers had maintained his average pace, his time would have been between 2:08:47-2:08:59, enough to be the fastest marathon in the world given the controversy around the world record set by Derek Clayton in 1969. Thanks to Bob Hodge via Facebook we have a photo of Rodgers running at the event, clearly showing the same red Onitsuka Tiger Ohbori racing flats that he had worn to such success in New York. Hodge plans to write an article about this event soon, which should fully explain this interesting and mysterious event!

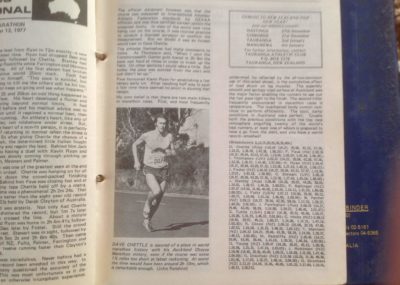

Then there was also the infamous Choysa International Marathon held in Auckland in 1977. The debut event was held in perfect conditions for running, and the course itself was relatively flat. The pace was astonishing, but few could believe it when David Chettle of Australia won in a sprint finish with a time of 2:02:24.

To put that time into perspective, the marathon world record at the time was 2:09:12, set by Ian Thompson at the 1974 Commonwealth Games, who coincidentally also took part in the event and ran 2:03:32 on his way to third. Even though Chettle was wearing what appeared to be the highly regarded Nike Elite, it was hardly comparable to the carbon-fibre plate Nike creations of recent years. In the immediate aftermath organisers found the course to be approximately 600 metres short, but during the next week more thorough investigations went ahead.

They found that the original course was measured one metre away from the curb of the road the entire distance. The sections around the city’s harbour were particularly wide and twisty, which in practice meant competitors could save considerable time running around the middle of the road. Taking into account the overall most efficient path along the course, they found it no less than 2,469 metres short of the marathon distance. It would have equated to around seven minutes extra time, impressive but not the marathon world record.

Organisers of the New York City Marathon were adamant that the more significant changes for 1982 did not affect the world record set by Salazar, saying that he ran along the middle the whole way and often had to take the long way to avoid crowds. They claimed video of the event, which is available online, proved their point. Nothing was said about the world records set by Waitz and Roe. For the moment all was well.

4. Closer scrutiny

That same year, the National Running Data Center (NRDC) launched a validation program for race courses where American records had been set. At the helm was Ken Young, who had initially been asked in 1971 to help an assistant coach for the United States Olympic Team arrange handicaps for an event the man had organised each year. Young asked Runner’s World for data on race results to help with the task, and was provided with boxes of information.

Young would go on to start the NRDC in 1973, even developing programs to help analyse the growing collection of data. By the time the validation program started, Young was serving as the official record keeper for the long distance running committee of The Athletics Congress, now known as USA Track & Field, the national governing body. It was a role he held from 1978 through to 1988. Young would eventually co-found the Association of Road Racing Statisticians (ARRS) in 2003.

Apart from being the largest database of race results in the world, it has allowed for analysis of which marathon events are the fastest. Young was also able to create the Competitive Point Level (CPL) system for athletes based on where they finished in their races. These calculations did not consider the time, only where an athlete finished compared with other athletes. When applied to hundreds of events, the CPL system predicted the winner 45 percent of the time, with the CPL leader finishing on the podium 79 percent of the time.

As it was back then in 1982, the NRDC validation program set the acceptable tolerance for courses where American records had been set to account for improvements in measurement standards. For the 1981 New York City Marathon, which was held between 1 April 1981 and 31 December 1983, that tolerance would be 0.2 percent or around 84 metres. For races held prior to 1 April 1981, the tolerance was set at 0.5% or around 211 metres. The Athletics Congress would bolster this move in 1983 by officially recognised marathon records for the first time. This included strict new certification rules as well as mandatory remeasurement.

5. Los Angeles hosts the Olympics

American authorities would apply this renewed focus on accuracy to another marathon. In 1984 the Olympics came to Los Angeles. It would not only host some of the strongest talent in the men’s event, but also see the women’s marathon take place for the first time in Olympic history with an equally strong field of competitors. The organisers wanted to make absolutely sure their course was as accurate as possible.Enter David Katz. The former science teacher had been involved in course measurement since 1974, and was appointed to the Amateur Athletics Union Standards Committee in 1977. He was part of the team conducting the measurements.

The team also included Tom Knight, another pioneer of course measurement. Together the group spent days figuring out the standard which they would use.Katz would later say it was the birth of accurate road course measuring in America. Using steel rulers and bicycles equipped with Jones Counters, calibrated to click a certain number of times per mile, the team would ensure that every inch was accounted for. Each intersection was carefully mapped out to ensure that athletes competing in the 1984 Olympic marathon had no doubts regarding the distance they ran.

6. The remeasurement

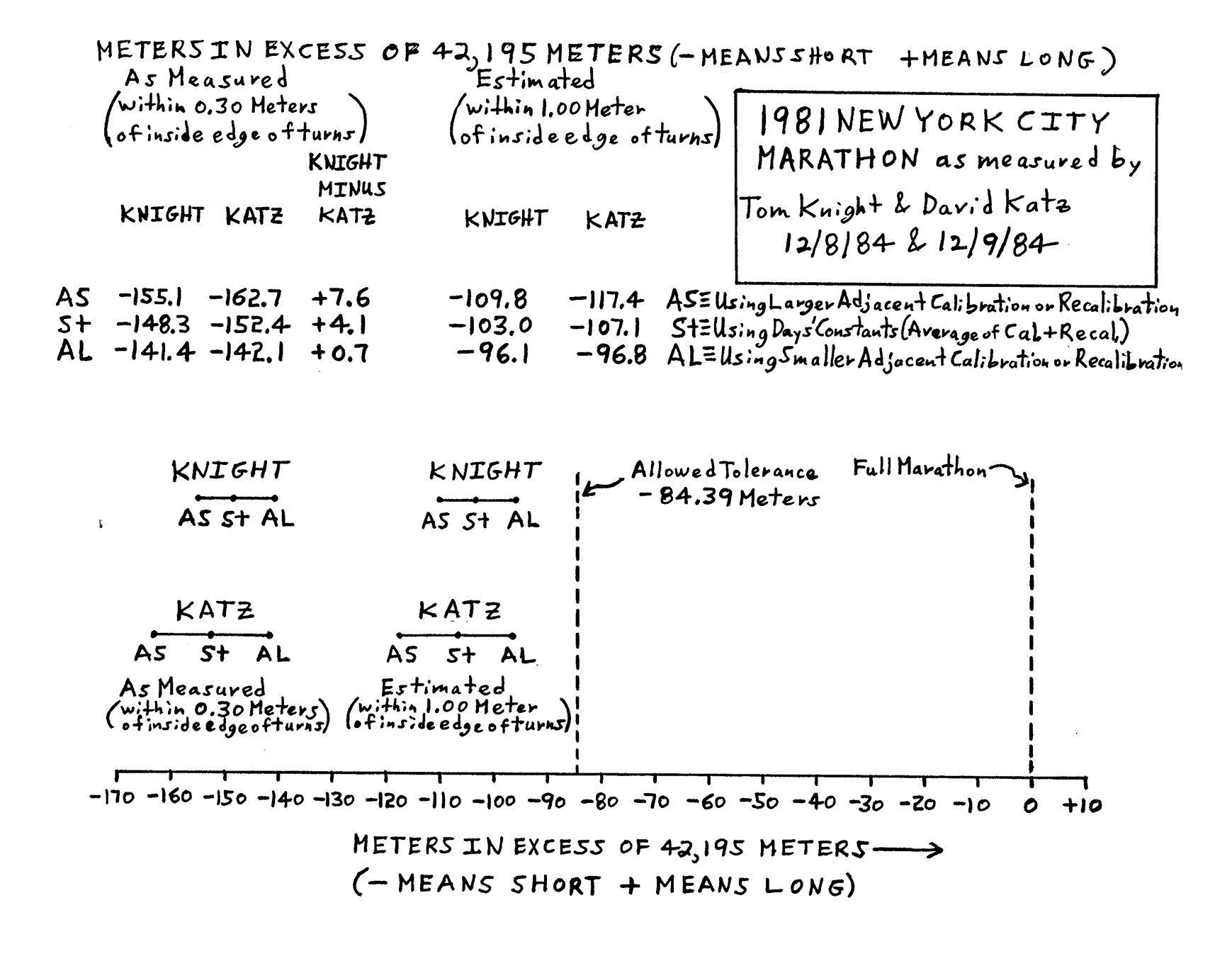

In the following months the NRDC turned their attention to the New York City Marathon, specifically the course used back in 1981 where the world records were set by Salazar and Roe. On December 8 and 9, Katz and Knight used the same exacting methods they had applied in Los Angeles to inspect the course. They took two measurements along the shortest possible line, not the middle of the road, at 0.3 metres from the curb and then one metre.

The results were clear. At 0.3 metres, Katz had the course 152.4 metres short and Knight 148.3 metres. At one metre, Katz calculated 107.1 metres and Knight 103 metres. It was plainly in excess of the allowed margin of 84 metres. Even the 1982 route came up short when Knight later remeasured it, by 12.8 metres and 58.8 metres from the 0.3 and one metre marks.

For the NRDC there was no question. The course that Salazar and Roe had set their world records on was short. The Los Angeles Times reported that in January 1985 officials had looked back on the old videotapes of the 1981 event to remeasure the exact path taken by Salazar, the one that organisers had claimed proved he had run the full marathon distance. The resulting distance was still short by approximately 50 yards or 45.72 metres.

This led The Athletics Congress to make the decision in late January 1985 to invalidate the records set by Salazar and Roe. Lebow said at the time that he would appeal the decision, saying the discrepancy in distance was within allowable limits at the time. The response back was that it was irrelevant that the course was certified to less stringent rules back in 1981, given the new certification guidelines introduced in 1983. History would show that Lebow was unsuccessful in his efforts to have the times reinstated. It should also be noted that by the certification standards that were applied, the world record times of Waitz would have still been allowable as the world record due to the 0.5% tolerance for races prior to 1 April 1981, however the simple fact is that the course was still short.

It should be further noted that the time Salazar had originally bettered was problematic in itself. The course that Clayton ran in Antwerp back in 1969 had been plagued by rumours it was short by as much as several kilometres. While the course was never formally remeasured, I confirmed through my research that the course was almost certainly around 430 metres short of the official marathon distance. You can read more about that in my article, however in any case the ARRS does not recognise the 1969 Antwerp Marathon results in their list of marathon world records. This meant the time to beat would have been 2:09:01, set by Gerard Nijboer in the 1980 Amsterdam Marathon. I note that since this article was published, World Athletics has removed the mark set at the 1969 Antwerp Marathon from the June 2024 edition of its ‘Progression of World Athletics Records’ book and instead now recognises the intermediate marks first proposed by the ARRS, including that of Nijboer.

7. Victims of their own success

Katz himself said that, given the retrospective nature of the rule changes, Salazar should have retained the world record. Salazar himself continues to insist that he ran the full marathon distance during the 1981 New York City Marathon. According to De Castella, the man who would be retrospectively given the world record, Lebow had apologised to him in 1990 for not admitting the course was short earlier. De Castella suggested that organisers had known about the issue before the re-measurement took place.

Back in 1985, Lebow wanted to ensure that the issues that had plagued the first marathon across the five boroughs of New York would not be repeated. In June of that year a team formed by the USA Track & Field Road Running Technical Council, which included Katz himself, laid out and measured the New York City Marathon course. The same exacting standards applied to the 1984 Olympics were applied to the streets of the New York, and there were no doubts that the 1985 event was anything other than the marathon distance.

Katz would go on to apply his skillset to ensuring the accuracy of the marathon at the 1996, 2012, and 2016 Olympics among countless other events. As noted previously, Young would go on to help found the ARRS, an invaluable resource for athletes, officials, race organisers, and researchers. It also features arguably the most accurate list for the men’s and women’s marathon world records.

None of this should detract from the significance of the New York City Marathon. It spurred the modern boom of urban marathons, turning such events into celebrations of the cities in which they are run. Part of this rise in popularity naturally led to increased scrutiny, especially with greater interest in the marathon world record. At the time this article was written, the men’s course record was 2:05:05, set in 2011 by Geoffrey Mutai in the Adidas AdiZero Feather.

The women’s course record at the time of writing is 2:22:31, set in 2003 by Margaret Okayo in the Fila Racer, the then-latest version of the first racing shoes to be equipped with carbon-fibre plates. That story is fascinating in itself, and I have written an extensive article on the history of these Fila shoes through Marathon Handbook, which you can find on their website.

| Embed from Getty Images | Embed from Getty Images |

It is in one sense unfortunate that the New York City Marathon had to be the event to set the example, but it hardly affected its success. It also meant that future marathons would not be plagued by doubts about accuracy. No less than 53,508 runners took the start of the 2019 New York City Marathon. That is quite the transformation from where things started back in 1970.

8. What if…

Hypothetically speaking, how fast would have Waitz, Salazar, and Roe have gone had the New York City Marathon course been properly measured? The various remeasurements conducted had the course as anywhere between 45.72 metres to 152.4 metres too long. Making the fairly big assumption that Waitz, Salazar, and Roe would have maintained their average pace for those last few metres, we can make some calculations.

Contemporary reports suggest that Salazar was in imperious form in 1981, intentionally easing off in the final miles to ensure victory. Roe had similarly few obstacles on her path to victory. Waitz however had suffered bravely during her three wins between 1978-1980. Nonetheless, she had powered to the finish each time.

In 1978, Waitz would have run somewhere between 2:32:39 to 2:33:02, instead of 2:32:29. This would still have been fast enough to set the new marathon world record over the benchmark of 2:34:47.5 set by Christa Vahlensieck in 1977.

In 1979, Waitz would have run somewhere between 2:27:43 to 2:28:05, instead of 2:27:33. That time would have still been the first time any woman ran the marathon faster than 2:30, and Waitz would have retained the marathon world record.

In 1980, Waitz would have run somewhere between 2:25:51 to 2:26:13, instead of 2:25:41.3. Again, that time might not have allowed Waitz to break the 2:26 barrier but it would have ensured she kept her place as the fastest woman to run the marathon.

Roe would have run somewhere between 2:25:39 to 2:26:01, instead of 2:25:28.8. This would have likely given Roe the honour of being the first woman faster than 2:26, and also would have stood as the marathon record until Waitz ran 2:25:29 at the 1983 London Marathon.

Finally, Salazar would have run somewhere between 2:08:21 and 2:08:41, instead of 2:08:12.7. It would have definitely been enough to take the marathon world record from Nijboer and potentially the disputed benchmark set by Clayton in 1969, but De Castella would have still taken it several months later with his 2:08:18 run at the 1981 Fukuoka Marathon.

It is understandable why the results from 1981 were invalidated, and why the ARRS does not recognise those times set previously by Waitz. It is unfortunate that World Athletics has not clarified this point in its own records. As it is, all three athletes achieved course records at one of the most iconic marathons in the world. That has not changed despite the miscalculations made regarding the course on which they ran.

References

Marathoning by Bill Rodgers with Joe Concannon

Marathon Woman by Kathrine Switzer

Bob Hodge via Facebook

Jenny Bahn via Facebook

Eric Giacoletto via Facebook

John Punshon via email

https://www.newyorker.com/sports/sporting-scene/the-first-five-borough-new-york-city-marathon

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/28/nyregion/george-spitz-civic-gadfly-helped-transform-marathon-dies-at-92.html

https://www.podiumrunner.com/culture/history-of-nyc-marathon/

https://www.nytimes.com/1982/10/22/sports/route-of-marathon-altered-in-brooklyn.html

https://www.runnersworld.com/news/a20802399/elite-course-measurer-im-a-real-pain-for-some-race-directors/

http://www.rrtc.net/Pete_Riegel_Archive.html

http://www.flrrt.com/london2012.htm

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/theres-more-to-measuring-an-olympic-course-than-just-measuring-it/

https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/09/sports/othersports/09measure.html

https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a20861716/the-endless-toil-of-the-big-data-guy/

https://aims-worldrunning.org/articles/748-ken-young-1942-2018.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1981/10/26/sports/2-world-records-set-as-13360-finish-marathon.html

https://www.lydiardacademy.org/photo-gallery

https://www.nyrr.org/Run/Photos-And-Stories/2018/The-Race-That-Changed-the-Face-of-Road-Racing

https://www.nydailynews.com/sports/more-sports/rodgers-won-five-borough-nyc-marathon-1976-article-1.2407192

https://www.nydailynews.com/sports/more-sports/zone-forty-years-nyc-organized-unthinkable-marathon-article-1.2860035

https://www.nytimes.com/1976/10/25/archives/new-yorks-first-citywide-marathon-draws-some-of-worlds-top-runners.html

https://www.runnersworld.com/advanced/a20856302/alberto-salazars-first-great-race/

http://ondekoza.com/aboutus.html

https://ausrunning.net/misc/victorian-marathon-club/newsletters/vmc-1978-autumn.pdf

https://www.thedeffest.com/vintage-ads/adidas-marathon-80-vintage-sneaker-ad

https://kicksoncards.tumblr.com/post/101636404527/grete-waitz-and-the-adidas-marathon-80-at-the

https://corp.asics.com/en/about_asics/history

http://sq210.blogspot.com/2014/04/nike-vintage-smus.html

https://k.sina.cn/article_2880525232_abb153b002000pzvx.html

http://www.billrodgersrunningcenter.com/privacypolicy.html

https://ftw.usatoday.com/2014/10/grete-waitz-nyc-marathon-adidas/grete-10