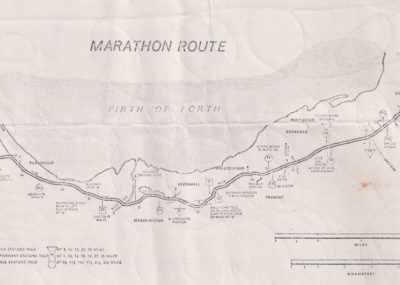

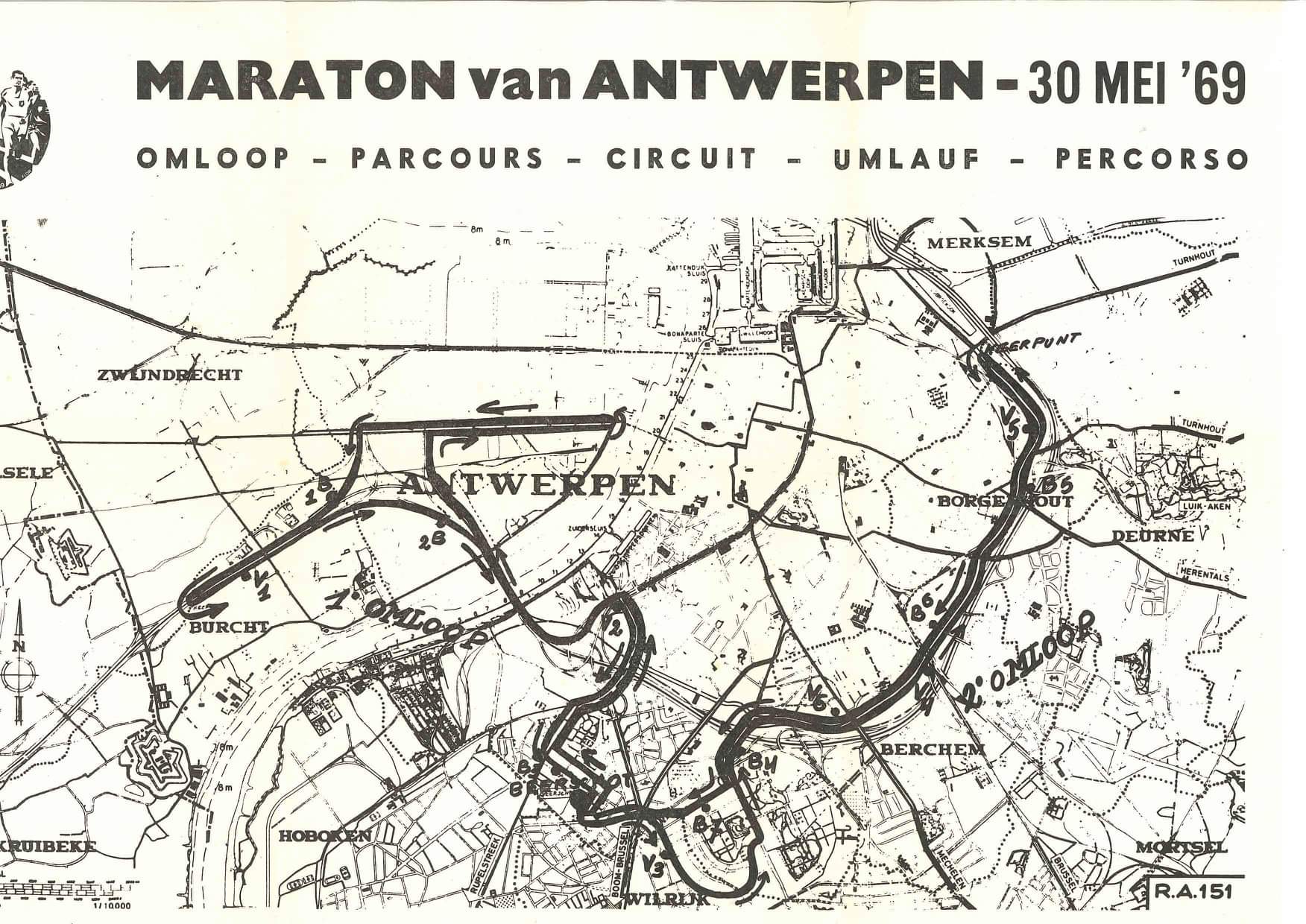

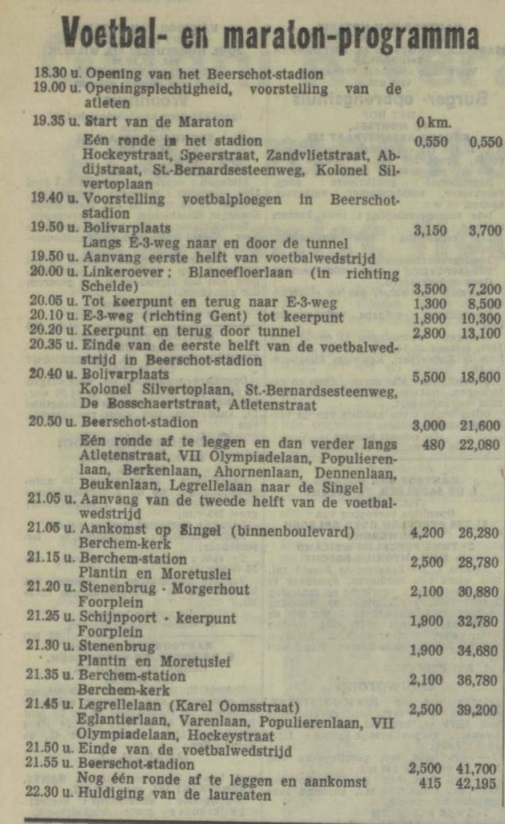

What you see here is the actual course map for the legendary 1969 Antwerp Marathon, published by the Gazet van Antwerpen who have confirmed to me that it is the genuine article. This document allows me to show that the course for the race was almost certainly around 430 metres short of the official marathon distance when measured against modern standards.

Based on the far more inaccurate standards of measurement that were in the official rules at the time, which were already in question by many as early as 1961, the course was approximately 300 metres over the official marathon distance. Before we get to this analysis, and why the more modern standard should be applied, let us look further into that legend.

1. An Australian in Antwerp

Legends have ways of defying attempts of uncovering the truth that underpin them. As the years go past, so do these chances. One such legend was the second marathon world record, or world best in the old parlance, of Derek Clayton. Having burst onto the Australian distance running scene, he further stamped his authority on the world when he won the 1967 Fukuoka Marathon. His time of 2:09:36.4 was nearly three minutes faster than the previous record set in 1965 by Morio Shigematsu. It would be the first time he ran the then fastest ever marathon.

Several years later, having unfortunately been unable to translate this pace into gold at the 1968 Olympics, Clayton was looking for another opportunity to prove himself. Across the world in Antwerp, the city and its people were looking for similar opportunities. After years of planning, and many more of construction, the long awaited Kennedy Tunnel would finally open. It was unclear why the tunnel was named after the former President of the United States, one of the lesser mysteries of this story.

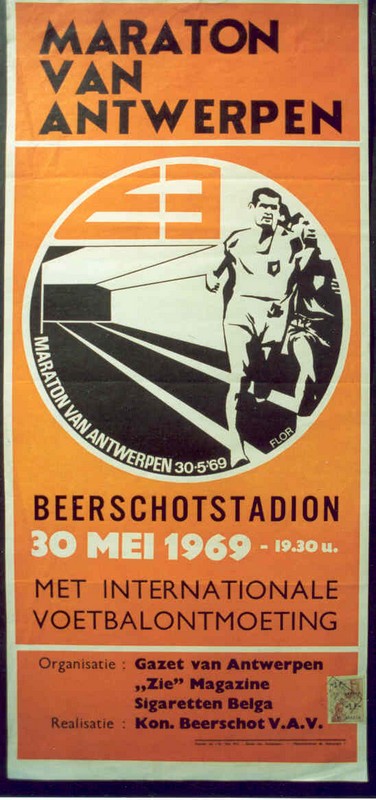

Supported by highways that ran along the former moats of the medieval city, the tunnel would provide unprecedented access to and from its neighbours. To celebrate this milestone, an idea was hatched by two local publications, the Gazet van Antwerpen and Zie Magazine: have the fastest distance runners in the world take on the marathon using these newly created roads to their fullest effect. They would be supported financially by the cigarette manufacturer Belga.

2. Belgium versus the World

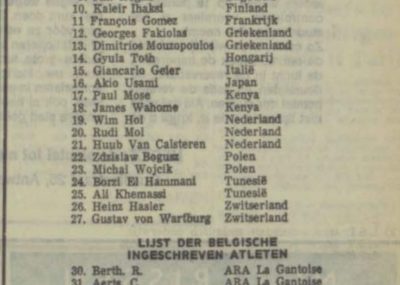

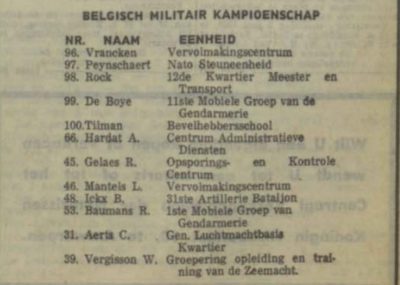

Organisers attracted the attention of Belgian athletics authorities, who agreed that the event would host the Belgian Marathon Championships. This meant pitting the best local talent against the cadre of invited international heavyweights from no less than 15 countries. Top of this list was Derek Clayton, whose trip to the event was paid for by authorities. He spoke with organisers beforehand who assured him the course would be flat and fast. Having upped his already considerable training in the months prior, Clayton believed the 2:07 mark was in reach.

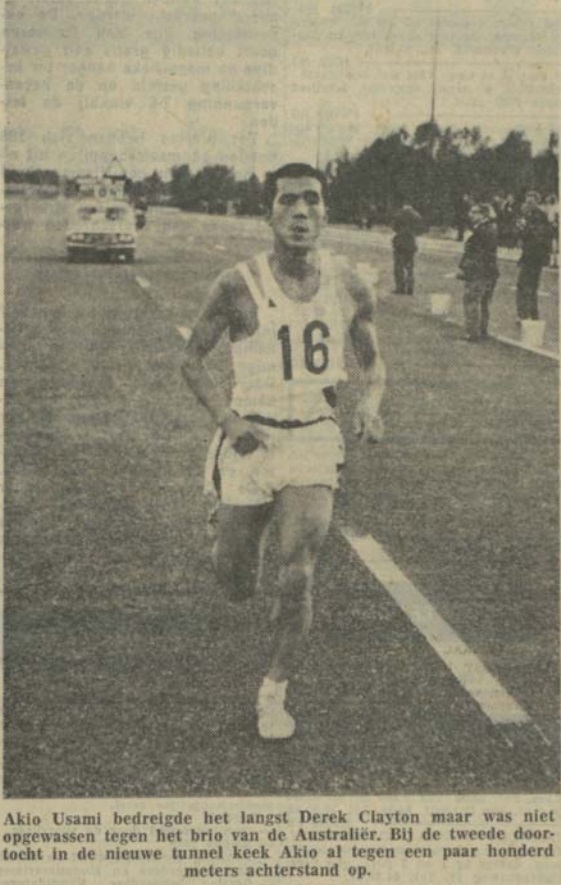

Come race day, alongside him were double Boston Marathon winner Aurèle Vandendriessche, Commonwealth gold medallist Jim Alder, European gold medallist Jim Hogan, and Japanese hotshot Akio Usami. Clayton and Usami were interviewed by the Gazet van Antwerpen leading up to the race, the Australian saying that they would be the top two by the end of the race.

Organisers took competitors around the course by bus to show them the flowing roads they would be racing over. Initial concerns were that the course was longer than the 42.195km distance that the marathon was officially set at since 1924. Come the night of 30 May 1969, the men lined up to take the start of the inaugural Maraton van Antwerpen. They would be starting at the Beerschot Stadium that had hosted the start and finish of the marathon at the 1920 Olympics.

3. Battle commences

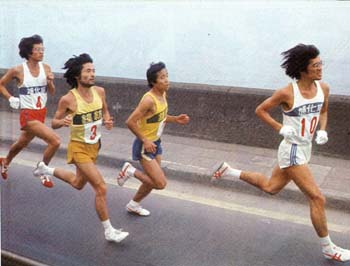

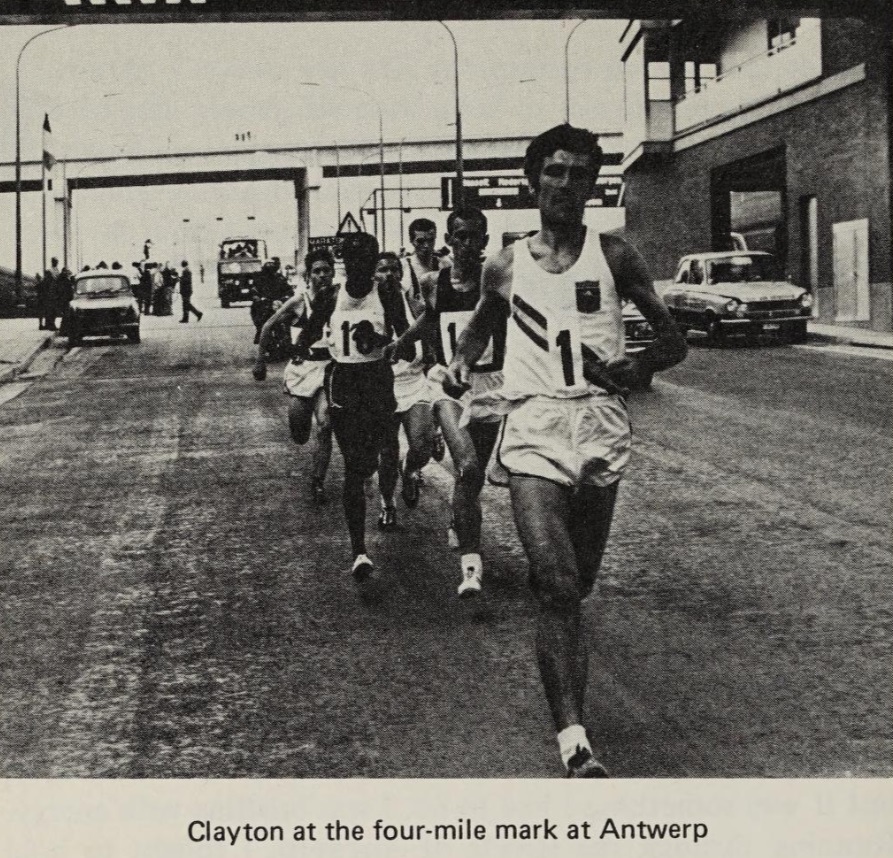

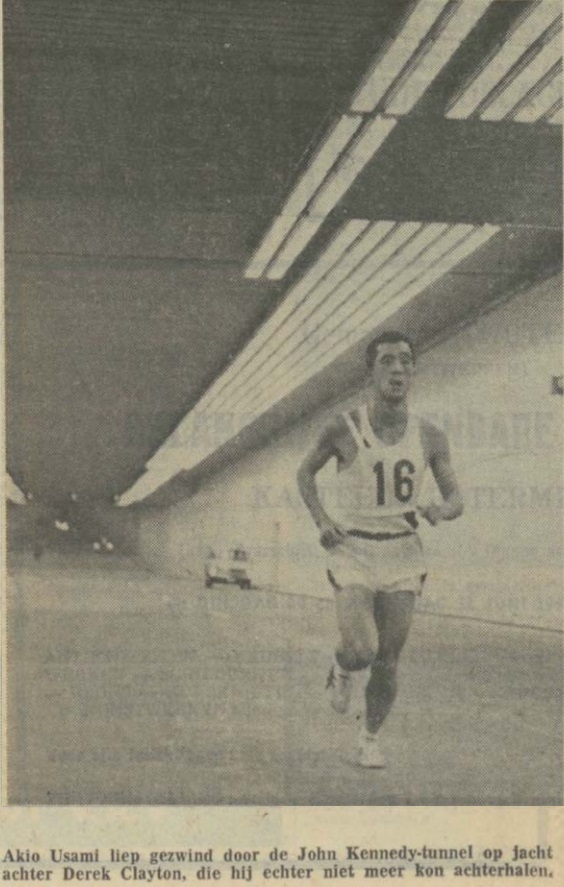

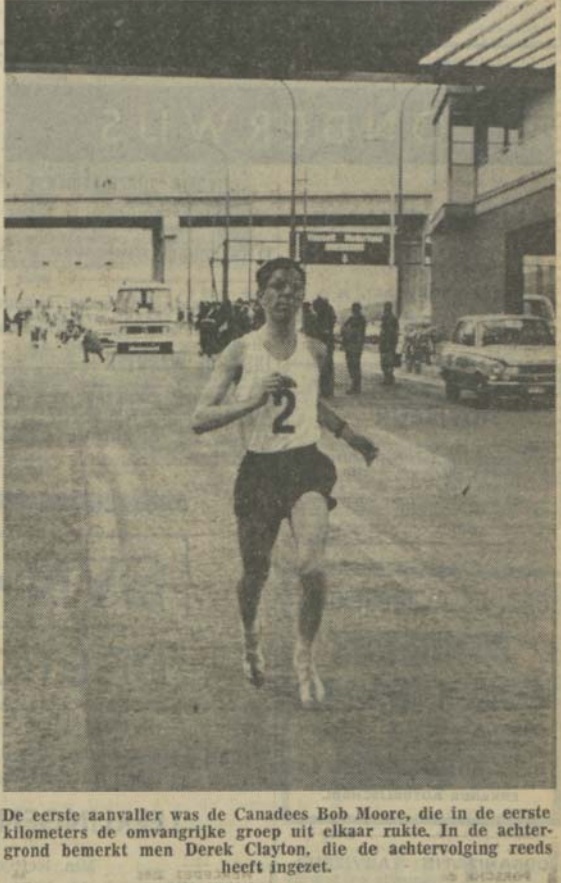

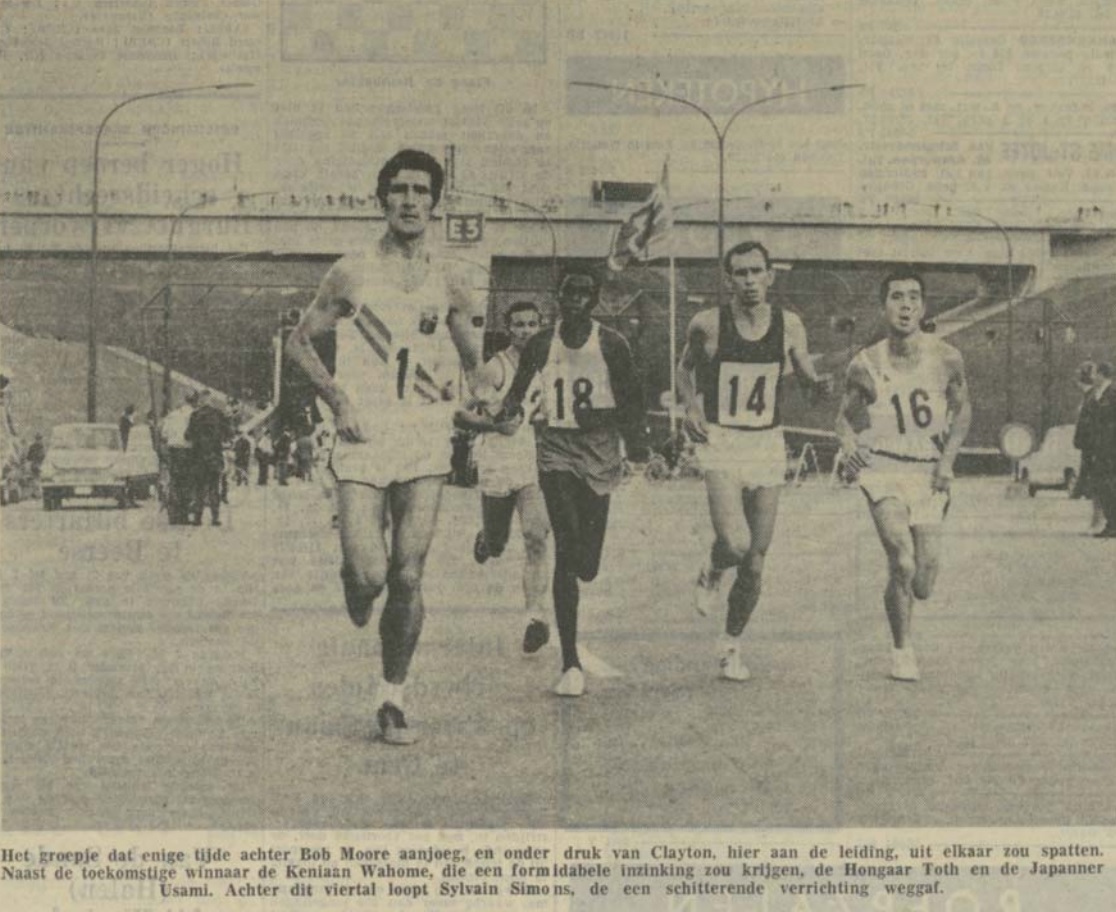

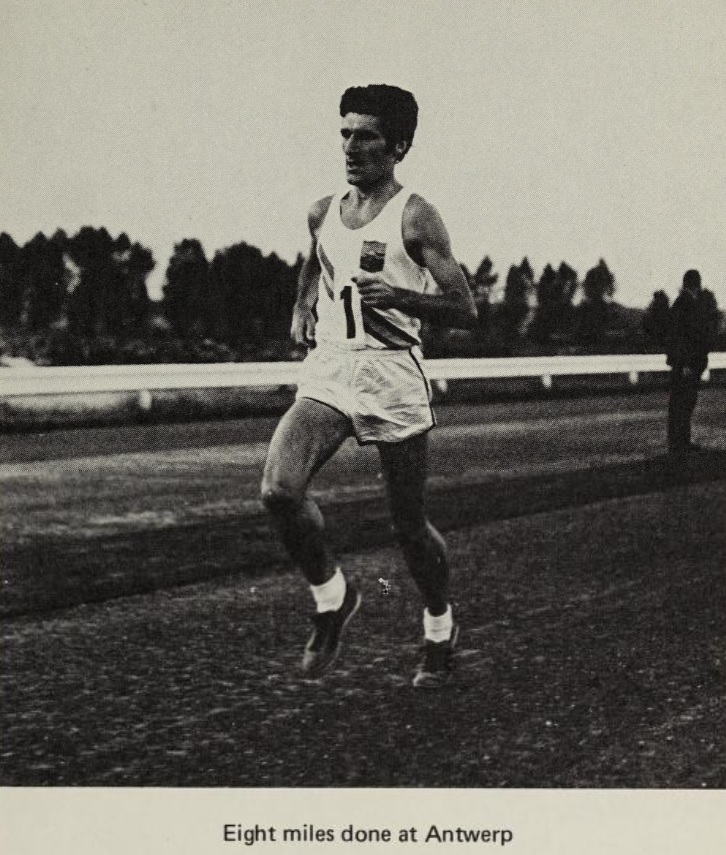

They were cheered on by nearly 15,000 spectators who had also come to see the football game to be played between the local Beerschot FC and the Bologna FC. The race began, the lead pack erupting out of the stadium and along the cobblestone streets of Antwerp. Soon reaching the Bolivarplaats square, they funnelled down the highway onramp and into the Kennedy Tunnel. The first 10 kilometres went by in an astonishing 29 minutes and 25 seconds, Bob Moore leading the pack. Clayton was close behind, having run the first leg in 30 minutes and six seconds. 2:07 still looked achievable for the Australian.

Moving further away from Antwerp, the runners would turn left off the Blancefloerlaan and onto Highway E3. This would later become an overpass, but at the time was a flat intersection. This is one of the few points where the original course has changed since that night, but more on those details later. After one of few hairpin turns along the course, the men were shot back towards the Kennedy Tunnel. From there it was back to the Beerschot Stadium, where they would complete another round during the half-time of the football match.

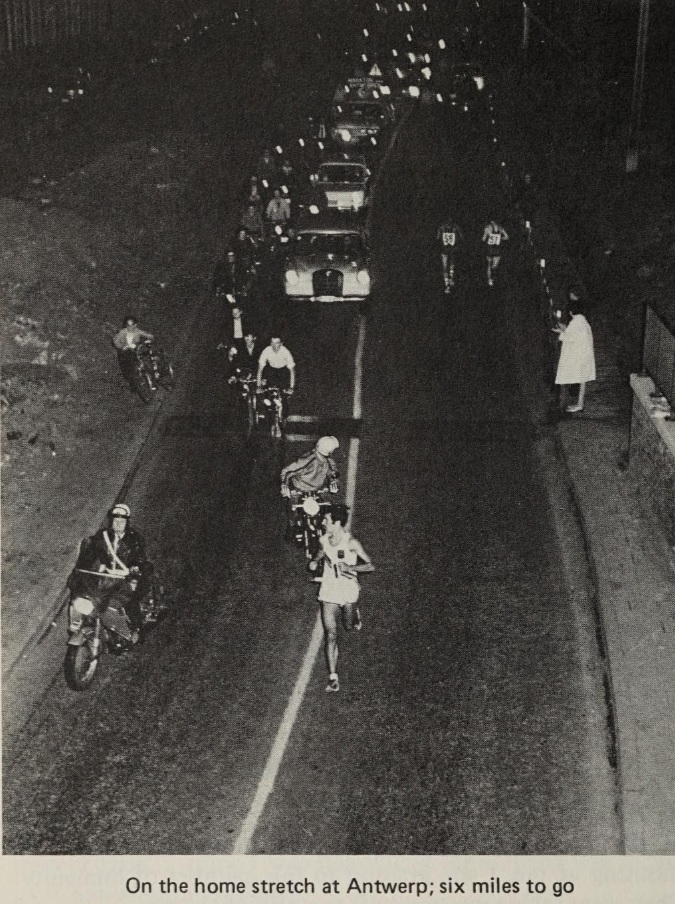

While the players could continue to rest, Clayton and his competition had no such luxury. They passed halfway in 1:03:55, the pace cooling ever so slightly but with Clayton still on track to set the new marathon world record. Runners would take on yet more of the newly built roads around Antwerp, this time curving around the outskirts of the city, flanked on one side by the newly constructed highway.

On their other side were glimpses of the old town itself, crowds gathering more and more as the race continued. Although police were given credit for helping block many of the roads, large crowds of cyclists started forming their own peloton and getting in the way of the runners themselves. Moore recalls having to hit several in the buttocks to get them to move out of the way.

4. Fighting to the finish

Behind the leaders the battle for the Belgian Marathon Championships was at boiling point, local hero Sylvain Simons slowly beginning to outpace retiring champion Maurice Peiren. They would both initially succumb around the ten kilometre mark to Vandendriessche, who mockingly yelled to Simons “see you later, brat!” as he accelerated away at one of the few hairpin turns on the course.

Simons would have the last laugh, although he would see his chance at winning the championship slip away at the 37th kilometre, Alder and Gyula Tóth passing him. Although finishing an impressive 8th and bettering his previous personal best by nearly fifteen minutes, it was Peiren who came out on top by finishing 6th.

They would make the last hairpin turn at the Schinport, or false gate, one of the last remnants of the medieval reinforcements that once protected Antwerp. It would be demolished the year after, now only the metro station name marking the location of the fortifications. Clayton had no time to ponder landmarks, his body starting to betray him as the final kilometres beckoned.

With three kilometres left, he began retching black bile, but the sight of the Beerschot Stadium drew him to the finish, and with one last lap of the grounds he crossed the line to win. He was told that he had finished in 2:08:33.6, more than one minute faster than his previous best. It would stand as the marathon world record for over 12 years until being beaten by another Australian, Robert de Castella.

Not everyone agreed.

5. Rumours and doubts

Almost as soon as the race ended, rumours began that the course was inaccurately measured and short by some considerable margin. Many tried to look into these rumours with varying levels of success. It is worthwhile spelling out some of these claims more specifically.

Ron Hill, another legendary distance runner, claimed his victory at the 1970 Commonwealth Games marathon was the real world best. He had heard the rumours and despite many attempts to contact Belgian authorities he had no luck.

John Jewell, secretary of the Road Runners Club of England and course measurement expert, spent two years looking into the race. He could only locate one newspaper report which according to him shed little light on the race.

Michael Chacour of the Road Runners Club of America similarly had limited success in his investigations. He was told by the Belgian Track Federation in 1980 that they had no files on record relating to the race, and that they did not organise the race either.

Manfred Steffny and Noel Tamini, publishers of Spiridon Magazine which was one of the preeminent running publications of the time, told Chacour that Belgian courses were generally measured by car. Specifically, they would average four car odometers to measure the course. The standard at the time was using calibrated wheels attached to bicycles to ensure accuracy.

Clayton himself was interviewed in 1980 by Chacour, who told him that officials advised him they measured the course with calibrated wheels attached to cars. The course was according to them found to be only six metres short. In an interview from 2019 with Roger Robinson, Clayton said he was later advised the course was found to be 80 metres long.

As it stood, many continued to question the validity of the Antwerp Marathon course. The Association of Road Running Statisticians, comprised of data experts and other senior figures in the running community, are one such voice. Many rumours and, apart from the 2019 interview with Clayton, no new information on the matter since 1980.

Until now.

6. Uncovering the evidence

In launching my website on the marathon world record, I had come past these discussions and was curious to see whether this was the end of the trail. My first step was contacting the Gazet van Antwerpen to see whether they had anything in their archives on the 1969 Antwerp Marathon.

They did. I was now figuratively holding in my hands countless articles that they had written on the event, photos that had not been seen in decades. There was also the schedule of the race, which listed the roads the course would take and the distance between each of these points.

Shocked that this information existed, I was encouraged to dig further. The other sponsor of the race was Zie Magazine, who surely had to have published their own articles on the race. It was off to the Belgian National Library, who have in their records all issues of the magazine.

With their assistance, those articles were soon open before me. Yet more images from the race, but no more information about the course. I attempted to map out the route using the list of streets, but despite my best efforts some of the checkpoints could not be aligned to the distance markings given.

Until finally, hidden away on Facebook of all places, I found the course map. It was uploaded by Paul Simons, son of Sylvain Simons. Even more incredibly, he would later provide me images of the May 2009 issue of the Dutch edition of Runner’s World Magazine, who published the exact same map. Suddenly the mystery of the course length looked very solvable indeed.

7. Measuring the course

To properly measure the course, I used the same standards applied to the remeasurement of the 1981 New York City Marathon. You can read more about the history of that matter in my article on this website. Suspected of being short, experts were brought in to measure the most efficient path throughout the course.

This is important, as this can result in much shorter distances compared with following the middle of the road. In that case, the course was up to 150 metres short of the required distance. The marathon world records set by Alberto Salazar and Allison Roe were invalidated accordingly.

Overlaying the 1969 map onto one of Antwerp published in 2001 and professionally scanned by the City Archives Antwerp, it was clear that for the most part the roads still aligned almost perfectly years later. I was able to further confirm this through other historical maps available through the City Archives Antwerp. Identifying the turnaround points was made simple by aligning the other roads visible on the older map. To be clear, there are still some differences and any liberty I have taken would have made the distance measured longer. I will spell out these now.

At the Bolivarplaats, in 1969 there was to my understanding an offramp from the square that led to the Kennedy Tunnel. This can be seen in the partial map of Antwerp from 1970 available online here. As mentioned previously, this offramp no longer exists following the construction of the Vlinderpaleis court complex. Next we have the first turnaround point on the Blancefloerlaan. The street list could be read as suggesting that this occurred two thirds of the way along, however the course map indicates this was at the very end near the Scheldt River. This corresponds to the other roads that are marked out in the map, particularly those that lead along the river.

Belgian authorities advised me that the left turn off the Blancefloerlaan that took runners towards the second turnaround point was a flat intersection until 1983 when the current highway overpass was opened.

This is one change that would unfortunately make exactly recreating the course today as it was back then effectively impossible. That being said, the newly built Parallelweg Zuid could now bring competitors from the Blancefloerlaan to the E17 highway with the overpass approaching the N419 highway bringing them back towards the Kennedy Tunnel.

Back in 1969, when runners returned back through the Kennedy Tunnel and towards Bolivarplaats, it appears they crossed back across the road to take the same highway onramp. Although concrete bollards are now in place, photos from the time (see above) show that these had not yet been installed.

That next turnaround point was identified through matching the side roads along the highway with the markings on the course map which indicated the location of those side roads based on their shape. These flank either side of the highway, the Lindenstraat on one side and the intersection of the Boskouter and Boomgaardstraat on the other.

These roads, which appear to have remained broadly unchanged since 1969, can be clearly seen in the 2001 map of Antwerp that I have primarily used for my analysis, noting again this was professionally scanned. Similar steps were taken in identifying the final turnaround point near the Schinport.

In the latter case, although the course map could be read as suggesting an earlier turnaround, the marker pen used could have confused matters. For the sake of clarity, I assumed the turnaround was in front of the Schinport so just at the intersection of the Binensingel where it meets Schinport Road. As with all of my assumptions, these make the course longer.

Lastly, although the majority of the roads in the back half of the course still exist, there are two differences that had to be accounted for. The first is the intersection of the Populierenlaan and Varenlaan which at the time connected smoothly but today is a much sharper turn using the Kruishofstraat to connect. This was accounted for in my measurements. You can see what the intersection looked like at the time in this map of Antwerp from 1970 professionally scanned by the City Archives Antwerp.

I’ve also assumed that the measured distance for the laps of the stadium are accurate. The detailed list of streets taken by the marathon route do not indicate whether the laps of the stadium included the distance from the street into the stadium itself, so part of my assumption is that this short distance was included in the measurements given.

Source: City Archives Antwerp, 12#12515

With all of this considered, noting that I used the most efficient path throughout these roads, I was able to mark out the route out using the Inkscape vector graphics editor software which allowed me to measure a line along the shortest possible route. Once this custom overlay was created, the software allowed me to verify how many pixels long it was down to two decimal places. An even higher resolution version of the map I used with the overlay of the most efficient route in red can be downloaded here.

Elsewhere in the map is the scale which I measured using the same technique of overlaying a line on the scale itself and then verifying how many pixels long this was. This allowed me to measure the course with considerable accuracy, no vagaries from having to use pen and paper. I’m happy to provide the high-resolution working file that was used, I have uploaded a comparatively low-resolution version for this website.

To reiterate, the map itself was professionally scanned by the City Archives Antwerp, so there is little risk of it having been warped in the process. There is the question of whether the profile of the course was such that overall it was the correct marathon distance. Without accurate height data from Antwerp during this period, this is not possible to verify.

Antwerp itself however is relatively flat so in my view it is unlikely the topography and therefore the profile of the route would have lengthened the course substantially, noting as well the highway sections would have only had mild gradients. I of course welcome such analysis if the data is available.

Finally, there is the question of whether the laps of the stadium were accurately measured. Given the other issues identified, there is every possibility that these may have been short as well and further shortened the course.

8. Coming up short

Comparing this against the scale of the map and how many pixels equalled one kilometre, the exact distance could be determined. The result is clear. The course used by the 1969 Antwerp Marathon was approximately 430 metres short. While exaggerated, with some having claimed the course was as much as two kilometres short, the rumours are true.

How did this happen?

Well, as Clayton recounted the organisers used cars with calibrated wheels attached. These are normally meant to be used with bicycles and there is an important reason for this. Cars have to follow an ultimately wider path around roads, the calibrated wheel could be at time two metres or more away from the most efficient route.

There is also the question of whether the measurement was taken from the middle of the road. The most infamous example of this was the 1977 Choysa Marathon in Auckland, where parts of the course were measured like this when the roads were particularly wide and curved. In that case suspicions arose almost immediately when David Chettle was able to win the race in an astonishing 2:02:24.

When measurements were taken using the most efficient route along the course, it was found to be no less than 2,469 metres short of the marathon distance. Then there was Michel Kousis’ new world record of 2:06:52.23 at the 1979 Mediterranean Games, which within one month was voided due to the course being assessed as having been 899 metres short.

Even the legendary Boston Marathon has fallen afoul of such issues in its past. World records set at the event between 1951 and 1956 (specifcally that of Keizo Yamada in 1953 and Antti Viskari in 1956) were later invalidated when it was found that due to improvements in the road at that time, with some previously curved sections being straightened, the course length had shrunk by 1082 metres.

Regardless of the scenario, there was unfortunately ample scope for organisers of the 1969 Antwerp Marathon to have inaccurately measured the course. Although Clayton, Alder and Simons all recall the course being remeasured after the race to verify the world record, it was clear that the methodology used by the race officials was suspect.

Keep in mind that World Athletics (known previously as the International Association of Athletics Federation) only first recognised the marathon world record officially in 2003, which brought with it additional scrutiny that simply did not exist back in 1969.

9. The most efficient route

Had the course been correctly measured, Clayton could have won in the high 2:09 bracket. This time would have been still incredibly fast, however given how he was fading towards the end of the race it was unlikely that he would have set the new marathon world record. What if however, like Alberto Salazar claims regarding his 1981 run, that Clayton did not take the most efficient route?

This is an interesting point, but even when the actual route Salazar took was analysed it was still 50 metres short of the marathon distance and that was taking into account an ultimately smaller shortcoming from the required 42.195 kilometres compared with the 1969 Antwerp Marathon. It is unlikely that Clayton ran anything other than the fastest possible route. He would not have settled for less given his expressed goal for the race.

There is also the point about Clayton’s splits during the race. They were 5km in 15:00, 10km in 30:06, 15km in 45:17, 20km in 1:00:30, 25km in 1:15:41, 30km in 1:30:56, 35km in 1:46:14, and 40km in 2:01:55. Clayton recalls having these times shouted at him during the race, but we have to remember those distances would have been based on those initially inaccurate measurements.

This would have resulted in approximately 50 metres extra distance between these five kilometre marks, which would not have caused any obvious discrepancy, the difference would have been around nine seconds. It was not like the Choysa Marathon where the result was obviously too fast, in fact until the last ten kilometres or so of the race the splits were slightly slower than what Clayton ran when he won the 1967 Fukuoka Marathon.

What about the improving standards of measurement for marathon courses? I apply the tolerance applied by the National Running Data Center which was applied in their validation program for American records that ultimately found the 1981 New York City Marathon course to be short. For marathons before 1 April 1981 this tolerance was 0.5% or 210.98 metres. More on that below.

Why is all of this important? Because facts are important. Removing the emotion that is tied to such incredible athletic endeavours, there is the unvarnished truth of whether the course was the 42.195 kilometre or 26.2 mile distance internationally recognised as the marathon.

Derek Clayton set the marathon world record at the 1967 Fukuoka Marathon. He is one of the greatest distance runners of all time, and almost certainly the greatest Australian to have taken part. His training schedule defies belief, having clocked as much as 255 kilometres in one week at his peak. What he did not do is better his time at the 1969 Antwerp Marathon. He won, but the course was short.

10. Changing standards

To reiterate, I’ve applied the standards used by the National Running Data Center (NRDC) when they assisted American authorities validate courses used to set American athletics records. Measuring using the shortest possible route, for races held prior to 1 April 1981, the tolerance was set at 0.5% or around 211 metres.

The previous rule set by the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF), known as World Athletics today, was that the course shall be measured one metre from the verge of the road and in the direction of the race. In practice the side of the road from which this metre was measured was the side that cars drove on in that country. In Belgium, cars drive on the right, and it is from this side that I measured the course using the old IAAF rule. This resulted in the course being approximately 42.5 kilometres in length or 300 metres longer than the official marathon distance.

The first course measured using standards closer to the shortest possible route (although still one metre from the verge whenever the shortest possible route came near) was the marathon course for the 1976 Olympics. This is explained in more detail in an article by Ron Wallingford, the Race Director for the event, which you can read here.

As for the NRDC validation program, the Boston Marathon course was assessed in 1983, noting that it had not to my knowledge been updated since changes were made in 1957 following road changes that had resulted in the course being 1082 metres short between 1951-1956. Even though the shortest possible route was measured, not the route set according to the old IAAF rule that would have applied in 1957, the course was found to only be one metre short. This was obviously well within the tolerance set by the NRDC.

With this being said, as early as 1961 it was known that the rule set by the IAAF could lead to inaccuracies. In an investigation of measuring standards by John Jewell, secretary of the Road Runners Club of England and course measurement expert, he observed that the rule is susceptible to individual interpretation particularly in regards to how corners are measured.

In his investigation he comments that many road courses in the United Kingdom have been measured “on the path actually followed by the runners” with general regard to the IAAF rule. To further quote from Jewell “This appeared the commonsense way of making the measurement. No one runs according to the Rule but according to the dictates of the circumstances, without running extra distance, and with regard to the traffic and considerations of sportsmanship.”

He later states that “different paths on the road probably make little difference in the course measurement” however it is clear this issue was known at the time of in the 1969 Antwerp Marathon. He further states that the largest acceptable error in measuring marathon courses is in his view approximately 156 metres. I note again the standard I’ve applied was the same used the NRDC when invalidating the world records set at the 1981 New York City Marathon.

There is the additional point about the method of measurement. As previously stated, Belgian authorities allegedly used car odometers to measure the course. Jewell in his 1961 investigation was scathing of this method, observing that “They are liable to considerable errors from various causes” and that “It is evident this method of direct reading from the instrument is unsuitable for course measurement.”

In summary, I’m more than comfortable with the standards I’ve applied to the 1969 Antwerp Marathon course. The considerable inaccuracies with the old IAAF rule are readily apparent for the course of the 1969 Antwerp Marathon, where there is the staggering difference of approximately 730 metres between the standard applied by the NRDC compared with the old rule.

As discussed above, it was not the case that this was the only standard applied, there were rumblings for some time that it could result in such discrepancies between the distance measured and those that the athletes actually ran. To reiterate, the Boston Marathon course features many curving roads that could have resulted in similar issues, however when formally measured in 1983 it was found entirely accurate.

It is clear from my research that the methods used to measure the course were not just deficient compared with modern standards, they did not even represent best practice at the time. This further assumes that the measurements were taken fully according to that rule, noting that it is likely car odometers were used which further puts at risk the accuracy of the measurement. It illustrates why it was so important that the standards of measurement were reconsidered and updated.

The athletes who competed in this event deserved better. Most of all Derek Clayton, who was all but promised the fastest marathon course in the world.

11. Ron Hill, Ian Thompson, Shigeru So, and Gerard Nijboer

Where does this leave us? Just as how Robert De Castella was retrospectively recognised as having held the mark after Alberto Salazar had his time disallowed, so too should the men who bettered Clayton’s mark at the 1967 Fukuoka Marathon.

They are Ron Hill, Ian Thompson, Shigeru So, and Gerard Nijboer.

Their achievements help illustrate the magnitude of the battle to break the 2:09 marathon mark, which was finally bettered by De Castella. They ran in an era that limited how athletes could monetise their fame, and holding the world record would have brought considerable opportunities both professional and financial.

It should be noted that this has been an issue for World Athletics for some time, regardless of this article. The official guide to world record progression published in 2020 by World Athletics did not include the 1969 Antwerp Marathon and Derek Clayton in its list for the marathon. It skips from his world record in 1967 to the mark set by Rob De Castella in 1981. The 1969 Antwerp Marathon is listed below this list in a supplement. It is noted “course short by 500m”.

I have been in touch with those close to World Athletics as part of research for this article, and my understanding is that the next edition of the Progression of World Athletics Records will likely amend the progression of the marathon world record to recognise Hill, Thompson, So, and Nijboer. I note that at the time of writing this is not the official position of World Athletics. Since this article was written I can however confirm that in the 2024 edition of the ‘Progression of World Athletics Records’ book published by World Athletics, they now include the marks set by Hill, Thompson, So, and Nijboer in the official world record progression for the marathon. The 1969 Antwerp Marathon remains in the supplement with the note regarding the course being short.

In the course of writing this article I was fortunate enough to speak with Moore and Wayne Yetman, who were both very helpful in providing further background details to the race itself. Although I attempted to speak with Clayton, I was advised that he understandably no longer wishes to speak about the event. I will only reiterate that this article is not intended in any way to diminish his legend.

12. What next?

There remains the understandable question of whether the previously discussed intermediate marks would withstand the same scrutiny faced by the 1969 Antwerp Marathon. I note that the ARRS has not noted any such suspicions against these other courses.

During my research I nonetheless came across course maps for these four intermediate marks. I would welcome these courses being subject to further scrutiny, however in my research there have been various challenges for future researchers that will be noted here.

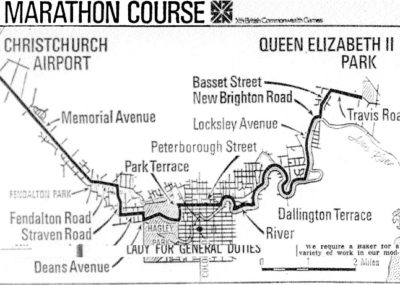

1970 Commonwealth Games: Although my initial analysis suggests the course is broadly accurate, the turnaround point for the 1970 Commonwealth Games course is unclear based on the course map, as is the route taken from the stadium to the roads making up the course. This is based on comparison against survey maps of Edinburgh from 1966 professionally scanned by the National Library of Scotland.

I have also spoken with Brian McAusland of the excellent website Scottish Distance Running History who confirmed that athletes took the equivalent of three laps of the stadium equalling 1.2 kilometres. It should also be noted that the course was used almost annually until 1980 for the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association national championship marathon. By this point verification standards would have been closer to what we expect today.

Further enquiries would be needed to confirm the turnaround point and route into the stadium, however I was unable to find further information in my research.

1974 Commonwealth Games: The accuracy of the 1974 Commonwealth Games course is less clear as there is no information about how many laps of the stadium were taken by competitors, and again what route was taken from the stadium to the roads making up the course.

Having conducted an initial measurement against a map of Christchurch from 1967 (which was professionally scanned by the National Library of New Zealand) it appears the course may have been short, but this needs to be subject to further scrutiny. I contacted the New Zealand Olympics Committee but with no luck.

1978 Beppu-Ōita Mainichi Marathon: I have unfortunately been unable to find a detailed course map for this race. The best I could locate was an image from the television broadcast of the 1982 event available on YouTube, noting it used the same course as in 1978 prior to organisers changing the route for 1983.

The map itself however does not clearly identify the finish, and watching the race itself was not enough to clearly identify the finish line or the turnaround point. I separately contacted the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper who have sponsored the event for decades, who were unable to locate a course map in their archives.

Noting that Japanese course measurement standards are among the most stringent in the world, in my view it is unlikely the course was short.

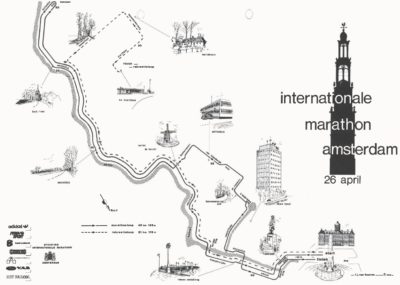

1980 Amsterdam Marathon: With thanks to the Amsterdam City Archives I was able to get the route map for the 1980 Amsterdam Marathon. The course for this event changed many times over the years, but initial analysis using Google Maps (which is based in part on satellite data) suggests the course was the required distance. It would of course be better if this analysis were made with a contemporaneous map of Amsterdam. It should be further noted that the course would have been subject to the more modern measurement standards of the time as well.

What if I have missed something? I welcome any further analysis of my findings, with all of the information included in this article. I’d be more than happy to supply the map files in full resolution to aid in this. If you have any other information about the race, I would be very interested to hear from you.

We take for granted the accuracy of marathon courses, but the journey to get to this point has been similarly long and arduous. It is one worth respecting as much as the athletes who have attempted such courses.

As for the organisers of the modern Antwerp Marathon, this also represents an opportunity to change their course to more accurately reflect the legendary path taken all those years ago. By the way, Clayton’s shoes were the Adidas Marathon, I’ve written more about in my profile on this website.

References

Gazet van Antwerpen

Zie Magazine

Running to the top by Derek Clayton

De avond van Derek Clayton by Ivan Sonck for Runner’s World Netherlands

A Night to Remember – Antwerp: May 30, 1969 by John Curtin for Canadian Runner

Running Encyclopedia by Richard Benyo and Joe Henderson

Bob Moore via email

Wayne Yetman via email

Roger Robinson via email

Paul Simons via Facebook

Nobby Hashizume via Facebook

Eric Giacoletto via Facebook

Conno du Fossé via Facebook

http://lynbrooksports.prepcaltrack.com/ATHLETICS/TRACK/2017/208_mar.pdf

https://lydiardtrainingandacademy.medium.com/runners-from-the-land-of-rising-sun-part-2-lydiard-connection-2da3f9da1b84

https://ausrunning.net/misc/victorian-marathon-club/newsletters/vmc-1978-autumn.pdf

https://www.nytimes.com/1979/10/21/archives/new-marathon-record-is-voided-by-short-course.html

https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a20801890/the-man-who-taught-me-everything/

http://idatenrunner.blog52.fc2.com/blog-entry-483.html

https://www.rrtc.net/Pete_Riegel_Archive.html

https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/CHP19740124.2.175.1

http://www.scottishdistancerunninghistory.scot/a-hardy-race-the-eighties/